My apartment contains so many handmade treasures: cloths embroidered by my mother, a hooked rug and wall hangings, quilts, sweaters, toques and mitts made by friends. Each of them is precious because they’ve been touched and worked on by friends or family. They are cherished for so much more than their practical utility.

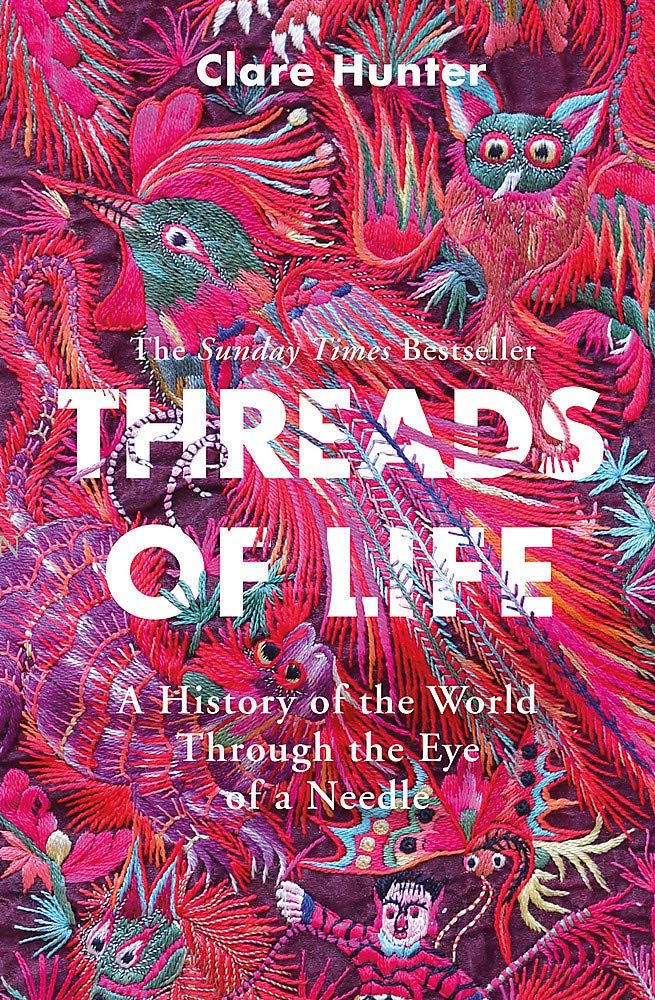

Clare Hunter is a textile artist who has used her skills to build community – from banners for striking coal miners to curtains designed and made by men with severe mental illness. Her book, Threads of Life: A History of the World Through the Eye of a Needle, recounts the many different ways in which textiles have been used throughout the ages. I was surprised by how varied the uses actually were, dismayed that far too often they were discounted as women’s work, and concerned that they could be abandoned in our age of electronic, factory-made objects.

The value and importance of rich fabrics and skillfully designed garments was clearly recognized in Renaissance portraits as “the artists who painted fabric were paid more than the portrait painter himself and were allowed access to the most expensive grades of paint.” In the 1600s, “embroidery was the visual language of the French elite. . . the most versatile form of visual messaging: displayable, wearable, portable, recyclable, they could carry information from place to place, from person to person.”

For women in captivity, embroidery has represented a means of self-expression and self-confirmation. Three women confined to mental asylums in the 19th century registered their strongly felt emotions by embroidering words on cloth or garments. Women confined to Japanese concentration camps during World War II collected and embroidered autographs, striking back against their fear of being eliminated or forgotten. They made quilts embroidered with images of all they held dear, passed along as hidden messages to their spouses in the neighbouring camp for men.

Banners are an important visual component of demonstrations and marches. Like the shoes and backpacks left on the steps of churches or legislatures, they create a powerful, long-lasting image. The 1908 suffragettes’ rally in London, England, was carefully crafted to counter the myth that the fight for the right to vote was a diversion for idle middle- and upper-class women. Women from all backgrounds (artists, surgeons, barmaids, homemakers) attended, and swirling above them were their banners. “Each silk-embroidered motif, hand-wrought, tasselled, appliquéd motif, was a visible refutation of the criticism that suffragettes were de-sexed and unfeminine.”

Other chapters of the book look at the role hand-crafted textiles have played in art, work, healing, and community-building. Each chapter is built on specific examples of individuals and their creations and it opened my eyes to the importance of hand-sewn objects that goes far beyond a pleasant leisure activity. Clare Hunter concludes Threads of Life with these words:

Fabric and thread can convey a prayer, trace out a map, proclaim a manifesto, send out a warning, bestow a blessing, celebrate a culture and commemorate lives lived and lost. Lives expressed not just through images but through texture and colour, different kinds of stitches, the various processes of piecing and patching, recycling, quilting to more clearly articulate the different layers of our humanity and manifest the fabric of our lives. Sewing is a way to mark our existence on cloth: patterning our place in the world, voicing our identity, sharing something of ourselves with others and leaving the indelible evidence of our presence in stitches held fast by our touch.

Community

I stumbled across two articles about community-driven memorials. They don’t use textiles, but the message of individual initiative and community-building is the same.

Wall of Love: The Amazing Story Behind the National Covid Memorial

A Lasting Legacy of Tolerance: Marcus Rashford Messages to be Preserved